How to Make History (More) Public

Posted on: June 8, 2022

In this blog Thomas Cauvin, author of Public History: A Textbook In Practice, explores what is meant by 'public history', and how we can go about making history more accessible to the public.

The past has never been so present. This somewhat provocative statement derives from the existence of so many representations of the past in museums and newspapers, at historic sites and on television and social media. The number of accounts dedicated to representations of the past on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, YouTube and other social media has skyrocketed over the past decade. Family history and genealogical research have perhaps never been so popular and dynamic. These activities testify that there is certainly no lack of popular interest in the past.

Paradoxically, in proportion to the level of interest in the past, the presence of trained historians in the public space is relatively limited. Even worse, the public space is full of ready-to-use statements and opinions about the past that reflect a general lack of historical understanding. In this post, I argue that instead of the usual academic criticism and disregard of non-scholarly and popular representations of the past, trained historians should learn how to make history more public. In relation to the publication of the second edition of Public History: a Textbook of Practice, I present public history as a way to better connect researchers, sites and institutions, communities and individuals to produce a new and enriched understanding of the past.

What Is Public History?

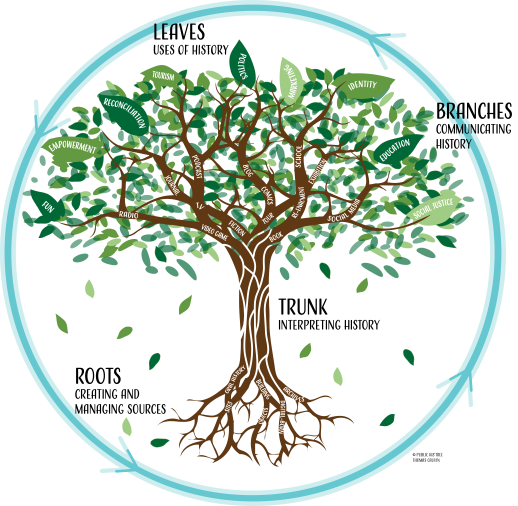

Public history is a process, a way of doing history that increases public accessibility, public engagement and public participation. Using the metaphor of a Public His’Tree (Figure 1), I argue that it is important to enlarge not only the definition but also the practice of history. While history is traditionally defined in academia as a rigorous interpretation of the past through archives – the trunk of the tree –, public history also includes the creation and preservation of sources (the roots of the tree) through methods such as oral history and historic preservation. Public history is therefore often performed and practised outside universities, in museums, archives, libraries and other cultural institutions.

Figure 1

Making history more public focuses very much on developing public accessibility. Public history therefore encourages practitioners to communicate their work beyond traditional journal articles and monographs. The Public His’Tree includes many branches representing different media through which history can be communicated. History can for instance be disseminated through exhibitions, podcasts, social media, guided tours, reenactments, games or graphic novels.

In fostering accessibility, public history also encourages more participatory and collaborative practices. Many public history projects are based on a shared authority in which researchers, curators, archivists, designers, video and radio producers, education officers, script writers and other professionals collaborate. Participation often goes beyond professionals and includes groups, communities and individuals who are interested in and/or know about the topic.

Accordingly, the textbook proposes four sections: a definition of the field and its current debates, the creation and management of public sources, the communication of history beyond academia, and the assets and challenges of working and collaborating with many different partners and stakeholders.

Making History Accessible to the Public

As a research process, history is not always easily accessible to non-specialists. Public history aims to develop accessibility beyond academia and research centres. However, just as teachers need to learn about pedagogy and class management, public history practitioners also need to learn skills to better connect researchers, producers, sources and audiences.

While trained historians have traditionally used texts – often in an academic writing style – to share their research, public history invites practitioners to broaden the range of media to reach more diverse audiences. The public history textbook includes chapters on how to use exhibitions, podcasts (figure 2), multimedia products, virtual environments, tours, graphic novels, blogs and social media to make history more accessible. The medium is not simply a matter of communication; it is also closely linked to the nature of the history being produced and presented and the way in which it is communicated. For instance, historical documentary films rely much more on visual (sites) and audio (oral history) sources than written productions. This in turn means that researchers must adapt their methodology and the way in which they gather sources.

Figure 2

Although accessibility is closely related to the selected medium, public history also relies on transversal skills and approaches. Public history texts often adopt a reader-friendly style, avoiding academic jargon, using short and direct sentences, and – when in a digital format – proposing hyperlinks in place of footnotes. Although academics have never lived in an ivory tower (contrary to the popular saying), it is true that trained historians could do a better job of connecting and engaging with a variety of audiences to make history more accessible.

For An Inclusive History-Making Process

As well as striving for greater accessibility, public history also aims to be more participatory. Supported by the rise of citizen science and collaborative practices in cultural institutions, public participation is receiving increasing attention from historians. Collaboration can make the history-making process more inclusive, opening projects up to diverse groups and participants. There needs to be an acknowledgement that the history-making process (from gathering and archiving sources to interpreting and communicating history) depends on who is – and who is not – involved, whose voices and interpretations are included or ignored.

More inclusive processes often result in the production of more diverse historical narratives. Involving the public in the collection of historical sources enables historians to go beyond official archives that often bear the mark of institutional power. The rise of community and radical archives is directly linked to the lack of diversity in (some) official and public archives. For instance, history harvests appeal to the public to bring personal objects and items to create or enrich archival collections. While most historians question official and dominant interpretations of the past, public history does so by collaborating and engaging publics in the process.

The rise of digital technology, especially the World Wide Web, has also had a major impact on who can participate in public history. User-centred and user-generated history has developed as a means of applying web technologies to the production of interpretations of the past. Digital crowdsourcing and citizen science provide new opportunities – although they also raise specific ethical issues – to make history more participatory and inclusive, and such approaches are, along with most public history practice, questioning and redefining notions of expertise and authority.

A more inclusive history-making process should not, however, deny trained historians’ expertise or encourage a relativist approach to the past in which not all opinions are seen as equally valid. Instead, public history calls for a combination of different types of expertise, with historians, designers, curators, historical witnesses, citizen historians and local residents all able to contribute to a richer understanding of the past.

Teaching Public History

If I were to be provocative, I would say that trained historians are not natural public history practitioners. They are sometimes quite uncomfortable with non-text media. Practising public history requires skills that are still very often missing in history training. As well as learning how to collect and interpret sources, students need to reflect upon the broader process of public history: how to create and preserve sources, communicate history through a variety of media and engage with present-day demands and concerns.

Public history training seeks to achieve a balance between theory and practice, rather than setting them against each other. Much like the “research through development” design strategy, public history invites students to design, develop and reflect upon projects for and with a variety of audiences. Projects offer opportunities for students to make their research accessible not (only) to their tutors but also to a broader audience beyond universities. These projects force students to take into consideration a variety of audiences and to show that their research matters, often giving them the opportunity to work with different types of partners in the process.

Making history (more) public is undoubtedly a process of teamwork that goes beyond disciplinary, institutional and national borders. In addition to making history more accessible, public history also empowers practitioners by providing them with opportunities for collaboration and coproduction. Collaboration does not mean giving up one’s own expertise; instead, it is about communicating and sharing authority with a variety of partners whose knowledge and skills can contribute to making our understanding of the past more diverse and more inclusive.